Working Party at Mogilno

On the 9th of September, thirty of us were issued with one third of a loaf and, after saying cheerio to all our mates, we paraded on the compound and moved off. We were cheered off by all the other men as was the practice when any party left. Upon arriving at the station at Schubin we were put in a cattle truck and we moved off at 8:00 am. After a very slow journey we arrived at Mogilno.

Mogilno was a very small town and in better times it would have been a peaceful, pretty place. When we alighted from the truck we were taken to a hut and given a bowl of soup, which was quite thick for a change! We were then marched through the town and came to a convent on the outskirts [Actually a Benedictine Monastery]. We were billeted ten to a room and given a loaf of bread between four – a big Polish loaf too. We thought that perhaps our luck had changed at last because we had been treated better this day than at any time since we had been captured.

The convent was built on top of a hill overlooking a very wide river. There was a twelve foot wall running along one side and then about thirty feet between the wall and the convent, which had a church adjoining it. This was locked to us and the guards. We had a good sized room with a stove in one corner. The Fuhrer (Officer I/C) came around to each room and said that we would get bunks later on and hoped we would be comfortable. That was the first time that anyone had said that to us. He was only a little chap but he seemed very human, especially considering what we had seen of the Germans so far. We had a meal of thick pea soup later and we all hoped that this was a good sign that this would be a good camp.

Our job was to build a barbed wire fence around the rest of the building, from the wall and get the place organised for a P.O.W. camp for more men who would come in later on. The camp was to be a base for road building.

That week, until the 15th was the best time I had known since early May. The food was better; thick pea soup, more bread (four to a loaf and Polish bread at that) and we received a lot more extras that the Poles slipped to us over the wall. Even the guards didn’t take much notice of this. When we had to go into town for anything the locals always put bread and tobacco in places where we would find it. We built two tiered bunks in each room and I had a top one in the corner. Although the windows were barred we had a fine view over the river which was about one hundred and fifty feet across. The guards were quite good and turned a blind eye to what was going on, when the Poles gave us things. Some evenings, when it was fine, they let us sit on a flat parapet on one side of the building. One chap in our room had a beautiful tenor voice and would stand on the edge singing songs like Ave Maria; it sounded lovely over the river as the sun set. (Poland had some of the most beautiful sunsets I have ever seen.) The Poles and the Germans had rowing boats on the river and they would stop for ages below us, listening to him. We closed our eyes, dreaming that everything was at peace and tried to forget where we were for a while. I think that was the most relaxing time of the whole period while I was out there. The work was easy and the guards didn’t bother us. However, alas, it couldn’t last.

On the 16th of September one hundred and seventy more men arrived. They brought with them a Red Cross parcel between three men, for us. It was a grand birthday present for me as I was 22 years old that day. I had a wonderful drink of tea and each one of the boys in our room gave me something from their parcels. Looking back on it now it seems strange what they gave me; one spoonful of sugar and jam, a square of chocolate, three or four prunes and so on. Little things they seem now but believe me they weren’t little things to us at the time. Food was the only thing we had to give and it was a sacrifice to part with anything of that sort. It was a birthday that I will never forget.

From then on it wasn’t quite so free and easy. The guards tightened up on the discipline (there were a lot more of them now) but the ones we had the previous week were still pretty good if they were on their own.

We now went on working parties to the road works. My job was to load a skip with earth, push it on rails for a quarter of a mile, empty it and go back again for another load. There were six men to a skip. In the mornings, when we got to site, the first thing we did was look in the skip and all around it because the Poles would put bread and fags there if they could. In time this stopped as the guards would go and look in all of them first and take out anything that had been left.

By the 23rd of September the Red Cross parcels were all finished. What a difference they made to our rations. Most of us paired up with another chap so that we shared what we got; it went further that way. Willie, the guard, gave us twenty four small fish that he had caught. We shared them in our room, boiled on our stove and they went down well. (although I don’t know what they were.) There was great excitement as some mail arrived. We all waited patiently until it was handed out but I waited in vain as there was nothing for me. How I envied the others who were lucky and received one.

The rations were in very short supply again and the Fuhrer was trying to get us extra. He seemed to be upset because we were short and came round to our rooms and apologised for not being able to get more. He said that he had to make do with what was sent to him. He seemed to be quite a good chap and fair, for a German.

On the 27th I had a good day. Three of us went into town to unload coal from a railway truck, with two guards, one of which was Willie. We finished early, at about dinner time. The Poles gave us thick pea soup with bread and instead of taking us back we just sat around until the usual time we would leave. The guards even got us some extra bread from somewhere.

Until the 13th of October the food was very short. Our Red Cross parcels were long since gone, the stew was watery (though thicker than at Schubin and Poznan) and it was six men to one of the small German loaves. We got a bit extra from the Poles, if we were lucky, and sometimes, if we were with Willie, he would slip us a packet of fags. Whatever one managed to get was shared out between us in our room. We were lucky in having a good crowd in our room who all mucked in well. Some rooms didn’t and this led to squabbling. Fights were fairly frequent when food was short and you always get the odd one who will try and take advantage. Coming back one day I caught one chap coming out of our room, which was empty at the time. He was only up to one thing and I got stuck in straight away. Then the others came along and he was a bit the worse for wear when he went.

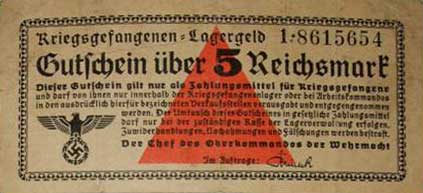

On the 13th of October we had our second Red Cross food parcel, one between two this time. I also got paid 7 Marks 35 Pfennigs so we could order bread now and it was brought to us from the village. We also bought razor blades, pencils, combs and notebooks; it made a big difference and everybody was feeling a lot happier. With the food from our parcels we made all sorts of concoctions. I made a cake from crushed biscuits mixed with raisins and a little dried egg powder; we thought it was smashing. Biscuits soaked and then fried made a nice change. (Although, much later when we had a Canadian parcel, the biscuits in them, when soaked, swelled up a lot thicker than the English ones.)

Poor old Willie got ten days confinement for getting us coffee on one job. Someone must have shopped him. He was one of the best Germans I met out there and was always trying to make things easier for us. I should think he was about 45 to 50 years old and he came from just outside Berlin.

He had a wife and two daughters. He hated the war and he didn’t have a good word for Hitler. However, as with all the others, he was scared to show too much familiarity towards us in front of the other guards.

Sunday the 27th. I obtained a Dutch hat and managed to get some water with which I had a lovely bath outside, in a bowl. We were all still very lousy and I kept thinking of how I should love to feel clean again. The old Fuhrer left and his replacement arrived. I wondered what he would be like – he didn’t look very special. It was bitterly cold. On the other side of the river there was a railway line and a lot of trucks were going by, loaded with armoured vehicles, covered in snow. The rumour was that they were going to Russia.

On the 1st of November it snowed quite heavily and covered everything. My old boots had nearly had it and the wet just poured in where I had cut them. I dreaded to think of going through the winter with them as my feet were already cold and the winter hadn’t started yet. The new Fuhrer was proving to be a right old so and so. He would get the guards to chase us out in the mornings with fixed bayonets and was shouting all the time. Nothing would please him and at the least little thing he would dish out extra work, or if it was an individual, he would give time in the cooler. I spent two days and nights in there on two occasions. One was for being late on parade and shouting “I’m coming you bloody goon!” He didn’t know what I said but guessed I wasn’t wishing him good morning. The other time I and my mate, Jack Baker, and three other men didn’t fill the skip full enough on one run and he happened to come along and see it. Also we answered him back. The guard got into trouble as well for letting us do it. (We used to put as little in the skip as possible so it was easier for us to push.) The cooler was in the coal cellar and it was dark, cold and very uncomfortable.

From the 22nd of November thousands of troops marched through Mogilno. Six of us were in there one day when a column marched through and there were a lot of brown shirts with them. One of them chased a Polish woman on the side of the street, knocked her down and started to beat her in the face with the butt of his rifle. He was shouting and screaming at her all the time but nobody took any notice of what he was doing. It was agonising to watch and be helpless to do anything.

On the 12th of December we went to the road works but it was too cold to do any work and the ground was frozen hard. We lit a fire and stayed there until it was time to go back.

The next day we left Mogilno to go to Schubin for de-lousing and stopped there for two days. After being de-loused we were issued with underclothing, mitts and socks (two more squares of flannel). I tried to get some boots and a shirt as well but was unsuccessful. We then left and returned to Mogilno at 4:30 pm.

On the 20th of December, thirty of us were told to dig up graves in a polish graveyard and break up all the headstones. We refused to do it, whereupon the guards cocked their rifles and took aim. We were scared they were going to fire but we didn’t move and still refused to dig up the graves. They then lowered their rifles and marched us back to camp, shouting and abusing us all the way. We were locked in the guardroom for the night with nothing to eat or drink. The next day we were marched back to the cemetery and told to get digging but again we refused. We went back to the guardroom and an argument took place between the Fuhrer and our camp leader. The outcome of it was that we were to just take the headstones to be broken up or we would be sent back to Schubin to be put before higher ranking German Officers where, our leader said, we might come off worse. At least we didn’t dig up any graves, which was what we objected to.

We had a Red Cross parcel, one between four men, on the 22nd, which was very welcome, and we were paid four Marks as well. More mail came but I was still unlucky as there was none for me. I wondered if the letter I had sent had arrived.