Finckenstein - late 1942

It was late at night when we arrived at Finckenstein and we were put into an old brewery. There were already a lot of other P.O.W.s there. In all we were just seventy strong at that farm. The brewery had two rooms for us to sleep and eat in etc. There were thirty five men to a room that had two tiered bunks around the walls. In one corner was a concrete drainage, about seven feet by four feet, and one foot high. The outlet was blocked up and was covered by boards. I don’t know what it was for originally but later on we made it into a stage for the band that we formed and the little plays that we put on. There was a large stove on one side of the room that could be used for cooking food from our Red Cross parcels. It was nowhere near as good as our billet at Lebanau. In between the two rooms was where the guards and the Commandant were billeted. Their accommodation was much better equipped than ours, of course. At night all the doors were locked and bolted.

There was a barbed wire fence around the front with about fifteen feet between the fence and the building. A cookhouse at one end and a toilet and cooler at the other end. We couldn’t use the toilet at night and we had a large bucket in each room. The one they gave us at first wasn’t big enough and overflowed so they gave us a bigger one but even that wasn’t big enough sometimes. It wasn’t very pleasant at the best of times. At night rats would run about the floor and we would sit on our bunks and throw things at them with shouts of “Got him, did you see him run?” or “Missed the *!*****!. We got used to them and no one was ever bitten, but we had to keep our food out of reach. We didn’t have any lice but there were loads of fleas and we couldn’t get rid of them, and did they bite too.

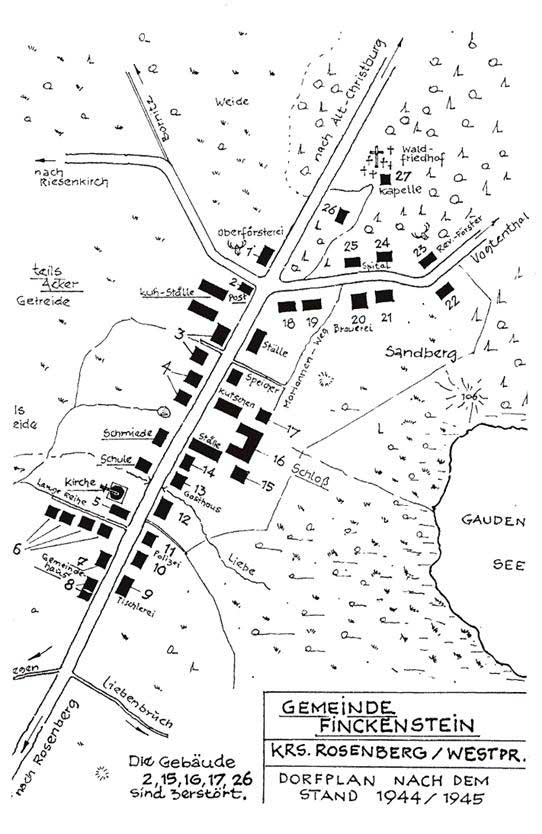

Finckenstein was a very small village where everybody worked on the farm for Baron Von Finckenstein, who lived in the Schloss (a big house on the same scale as one of our stately homes in England). Everything in the village was owned by him and there were about twenty cottages. When we had been there for a while we were told by the German civilians that some of them had never been outside the farm in their lives and a lot of them had inter-married. I imagine it was like an old feudal estate.

Each morning we had to march to the Schloss and line up outside the gates for our orders for the day. The Baron was always there, although he didn’t give the orders, but left it to the overseers. This included the civilians as well. He was a fat old *!****!, a very typical Prussian. The first day, while walking to the Schloss in the morning, we passed some civilian women who spat at us and shouted something (most likely not very complimentary).

Four days after I arrived there, on the 27th of April, I was suffering with toothache again and I asked our medical orderly to pull it out for me as it was so bad. He wouldn’t, because he said that he had no facilities to do it, but he managed, after an argument with the Commandant, for me to go with three others into the town to have it out. It was another woman dentist but this time she had no cocaine at all, so two held me down while she pulled it out. I thought she was pulling my head off but, after I got over the shock of it, I was glad it was out. On the way back the guard stopped the wagon at a Gasthaus (Inn) and bought us all a beer, although we had to stop on the wagon to drink it. It went down really well but I would have enjoyed it even more without the sore mouth.

Until the 12th of July we were mostly dung loading, rube hacking and kartoffel hacking. (Rube are turnips and kartoffel are potatoes; hacking is hoeing them up and spacing them out). We also had to do sugar beet and turnip singling which meant going along the rows on our hands and knees, singling out the plants to leave one every nine inches or so. We worked two rows per man and they went on for miles. The guards and civilians in charge came up behind us watching and would often shout “Eine eine bleiben, nicht schwei!!” (leave one, not two!) and back we would have to go, to take out the offending one and leave just one standing. Needless to say, when we could, we took out a lot more than one in nine inches, sometimes leaving quite big gaps. If they spotted them there would be hell to pay. It seems a small thing to cause trouble but we were pleased to think that there would be a few less for the Germans to eat.

Whenever we were on jobs in the fields we were always in one line, two rows per man with perhaps thirty to forty P.O.W.s and about twenty to thirty women, with the guards and overseers behind us. The German women were treated just like us, it was just like slavery. One day there were six Polish girls who had come from the town to work for a while. One in particular was very young and, while we were hoeing turnips, I happened to be on the end of the line of P.O.W.s. She was next to me and I noticed that she was crying. I asked her what was wrong, she couldn’t understand of course, but I guess she knew what I had said from the tone of my voice. She showed me her hands and they were just one mass of blisters, no wonder she was crying. I started to do her rows as well as mine and kept it up all day when the guards and overseers weren’t looking. She said something, I don’t know what it was, but the look was enough to know she was grateful. I tried to get her to understand to be in the same place the next day and she must have got the idea because she was next to me for the next three days. I helped her each day but then we were taken off that job and I didn’t see her any more, I think they must have gone back to the town.

At some periods we had a food parcel each week, sometimes one between two and at other times ,none at all. When we had regular supplies things seemed to go much better but, when they were short, morale quickly dropped and tempers became strained. The result was more fights and more trouble with the guards. Food governed most of our moods and was constantly on our minds.

The German civilians were, on the whole, better than those at Lebanau but there were the odd ones who we could never get on with, or them with us. Also several women who hated the sight of us – perhaps they had lost sons, I don’t know.

On July 5th we had permission to go swimming in a lake about a mile away. When we arrived there, we found several male and female civilians sitting around. We waited but they didn’t seem to be going and in the end we just went in and had a fine swim. We didn’t have any swimming trunks so the girls had a grandstand view that day. It was a lovely lake, about half a mile across and roughly circular in shape. It was surrounded by trees and grassy banks. The lake was a bit weedy in places but where it was clear it was fine for swimming and we thoroughly enjoyed it.

The food wasn’t very good there, with four men to one of the small German black loaves and the stews contained very little. We were paid on several occasions and were able to buy sauce, pencils, paper, combs, razor blades and beer. The beer was rationed at so much per man, varying from one bottle to three (If we could get it, that is). Six of us did alright on the 21st when we were chopping wood at the Gasthaus and we were given four bottles of beer each and five bottles the next day by the manager. He seemed very friendly towards us which was very unusual for a civilian.

On the 31st of July we started the harvest, binding and stooking, and got it all in by the 29th of August. There was no trouble to speak of and during the last few days the Baron sent out some beer for us and the civilians. He must have been in a good mood! The next day we went swimming again. It was very hot and we were brown as berries. The summers there are not changeable like at home and when it is dry it stays that way for weeks on end. When we arrived at the lake there were a lot of girls there but we didn’t bother this time and went straight in and enjoyed our swim. We noticed that they didn’t go away and seemed to be very interested in us! It was a very popular spot and there seemed to be quite a few dotted around the banks, sunbathing and swimming.

Most of the time until the 8th of September was spent dung spreading and then we went on threshing and carrying the sacks of corn up two or three flights of stairs in the barn. The oats were quite light but the barley and wheat were very heavy. I don’t know how we staggered up the last few steps. Several, including me, didn’t and then there were shouts and threats from guards and civilians alike. We used to like being on the threshing machine because we could fill our pockets with wheat and when we got it back to the billet would grind it up in a small hand coffee grinder and use as flour to make cakes. The coffee grinder was in constant use but it was slow work.

On Monday in the last week of October we went pulling sugar beet. It was bitterly cold and when we started we couldn’t feel our hands, they were so cold. We would go hell for leather until we got warmed up and then slow down to a steady pace but those fields just seemed endless. I had my first two days and nights in the cooler then. I had just got back from a particularly bad day in the fields and was feeling tired and fed up. I was lying on my bunk when the guard came in and ordered me to get up and clean the Commandants office. I swore at him and told him to “Weg-gehan, ich bin crank!!” He shouted but I still refused to move. The Commandant then came in and made me go to the cooler. It wasn’t very comfortable in there; it was cold and dark and I just had coffee and bread in the morning. I never did clean out his office though. Anyone coming out of the cooler always got a good reception from the lads and the cook always managed to give him a hot mug of tea and an extra meal.

Jack was very ill with fever and the medical orderly said to give him as much blackcurrant puree as he would take. Having given him all ours, I tried to get some from a chap who had several tins and offered him 50 fags a tin, which was well over the trading price, but he said he wanted it all for himself. We had one hell of an argument and it finished up in a fight. He was bigger than me but I was so mad and desperate to get a tin that I came off best and got a tin for nothing. However, Jack got worse and eventually had to go to hospital. It wasn’t usual for anyone to refuse to help someone that was really sick, but that man wouldn’t help anyone and he was always on his own.

On Saturday the 14th I went to Riesenburg and had another tooth out, on the 18th, had one filled and on the 21st had another one out. There was still no cocaine but they gave me the afternoon off work this time. I was beginning to think I wouldn’t have any teeth left at this rate.

On the 24th of November and the next two days, I was on my own with Karl, doing odd jobs. Karl was about sixteen years old and was one of the “good ones”. He bought me some eggs and we had a very cushy time. We spent a lot of time swapping English and German words. I was with him on the 5th of December as well and we caught a pigeon which I had for my tea. By now it had started to snow heavily.

On Sunday the 15th of December poor old Graff died. We buried him on the 18th in the local cemetery. He had been going downhill for a long time and had lost interest in everything. He was one of the oldest there.

On Christmas Eve we had a sing song and fixed up a stage in the corner of our room, over the drainage pit. We had a concert in the evening on Christmas Day in which we had a western theme. I had helped beforehand to make the cowboy hats and chaps, which we made out of old clothes, cardboard and any other bits and pieces we could scrounge. For Christmas Dinner, everybody put a tin of something into the cookhouse and the cook made a lovely meal which we had in our room all together. The cook was Vic Osbourne who cooked for us at Lebanau. I stayed in bed for most of Boxing Day and later we had a whist drive, followed by a dance in the evening. It was going well until the guards came in at 9:30 pm. We gave them a rousing reception but it didn’t make any difference and they wouldn’t put the lights back on. Although we had a good time over Christmas, it didn’t stop us thinking of home. We tried to make the best of things and hoped that this was the last Christmas we would have out there.

On New Years Eve we worked in the morning but had the afternoon off. We had a concert and dance in the evening that started at 6:30 pm and finished at 12:30 am. Three of us ended up sleeping in one bed. I’m not sure why but it might be that we had too much to drink as we had been saving up our beer for Christmas.